Bikes, fascists, war, and peace

For the last few weeks I've been reading and reading about two of my favorite creative manly men who rolled around on bikes: Pablo Picasso and Ernest Hemingway. Both changed the way we perceive the world around us. Both should inspire rollers to change that world.

For the last few weeks I've been reading and reading about two of my favorite creative manly men who rolled around on bikes: Pablo Picasso and Ernest Hemingway. Both changed the way we perceive the world around us. Both should inspire rollers to change that world. Hemingway, with his spare prose and knack for being in the wrong place (read: war zone) at the right time, introduced the journalistic style to literature. His short story, Old Man at the Bridge, blew me away after I got back from Bosnia-Herzegovina in the mid-90s. His encounter with an old man fleeing Franco's advance on his village during the Spanish Civil War captured the profound bewilderment I witnessed from working with the women and children who had fled the Srebrenica Massacre.

Hemingway, with his spare prose and knack for being in the wrong place (read: war zone) at the right time, introduced the journalistic style to literature. His short story, Old Man at the Bridge, blew me away after I got back from Bosnia-Herzegovina in the mid-90s. His encounter with an old man fleeing Franco's advance on his village during the Spanish Civil War captured the profound bewilderment I witnessed from working with the women and children who had fled the Srebrenica Massacre.In 1927, Hemingway went to Italy to report on the rise of Mussolini and the Fascists. Early in his career and practically penniless, he rolled around by bike as well as driving. Years later he would write,

It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best, since you have to sweat up the hills and coast down them. Thus you remember them as they actually are, while in a motor car only a high hill impresses you, and you have no such accurate remembrance of country you have driven through as you gain by riding a bicycle.His account caused a sensation when it was first published. It later became the basis of Hemingway's short story, Che Ti Dice La Patria? I am posting a portion describing his encounter with a Fascist on bike.

There was a sign with a picture of an S-turn and Svolta Pericolosa. The road curved around the headland and the wind blew through the crack in the wind-shield. Below the cape was a flat stretch beside the sea. The wind had dried the mud and the wheels were beginning to lift dust. On the flat road we passed a Fascist riding a bicycle, a heavy revolver in a holster on his back. He held the middle of the road on his bicycle and we turned out for him. He looked up at us as we passed. Ahead there was a railway crossing, and as we came toward it the gates went down.

As we waited, the Fascist came up on his bicycle. The train went by and Guy started the engine.

"Wait," the bicycle man shouted from behind the car. "Your number's dirty."He took out a receipt book, made in duplicate, and perforated, so one side could be given to the customer, and the other side filled in and kept as a stub. There was no carbon to record what the customer's ticket said.

I got out with a rag. The number had been cleaned at lunch.

"You can read it," I said.

"You think so?"

"Read it."

"I cannot read it. It is dirty."

I wiped it oft with the rag.

"How's that?"

"Twenty-five lire."

"What?" I said. "You could have read it. It's only dirty from the state of the roads."

"You don't like Italian roads?"

"They are dirty."

"Fifty lire." He spat in the road. "Your car is dirty and you are dirty, too."

"Good. And give me a receipt with your name."

"Give me fifty lire."

He wrote in indelible pencil, tore out the slip and handed it to me. I read it.

"This is for twenty-five lire."

"A mistake," he said, and changed the twenty-five to fifty.

"And now the other side. Make it fifty in the part you keep." He smiled a beautiful Italian smile and wrote something on the receipt stub, holding it so I could not see.

"Go on," he said, "before your number gets dirty again."

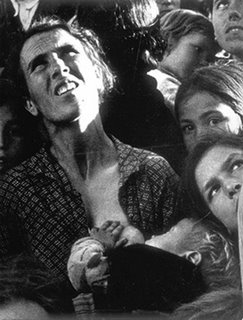

Picasso, by no means an ideological fanatic, nevertheless was the leading humanist of the 20th Century art world. His Guernica, although calling attention to the brutalities of the Spanish Civil War in Basque Country, remains a timeless condemnation of wartime civilian suffering. Just compare these two photos. The first is from the Spainish Civil War, the second from the recent conflict in lebanon.

Picasso, by no means an ideological fanatic, nevertheless was the leading humanist of the 20th Century art world. His Guernica, although calling attention to the brutalities of the Spanish Civil War in Basque Country, remains a timeless condemnation of wartime civilian suffering. Just compare these two photos. The first is from the Spainish Civil War, the second from the recent conflict in lebanon.

Less than a century separates them.

Labels: critical mass, history, pax, serious shit, war stories

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home