Back to Berlin with an anti-tourist

I realize there hasn't been much lately on books or on Isaiah Berlin either. It's not that I've stopped reading this summer. Much to the contrary: I'm a dipper who usually reads 3 or 4 books at a time. I try to balance the serious, long reads on philosophy or politics with the lighter stuff: historical novels or short story collections.

I realize there hasn't been much lately on books or on Isaiah Berlin either. It's not that I've stopped reading this summer. Much to the contrary: I'm a dipper who usually reads 3 or 4 books at a time. I try to balance the serious, long reads on philosophy or politics with the lighter stuff: historical novels or short story collections. In the last few months I've stacked up my current reads in the living room and bedroom. Both stacks, typical of a fox, include books on Web 2.o, the Soviet experience of WWII, obscure historical figures, and bizarre travel adventures.

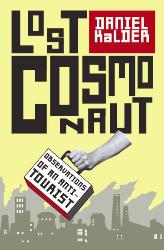

In the last few months I've stacked up my current reads in the living room and bedroom. Both stacks, typical of a fox, include books on Web 2.o, the Soviet experience of WWII, obscure historical figures, and bizarre travel adventures. I just finished a book in that last category: Daniel Kalder's Lost Cosomonaut: Observations of an Anti-Tourist. I discovered it in a review at the Times Literary Supplement website. It is his first book in what I hope will be a prolific career. Kalder is a 20something Scot who has just returned from a five year stint working and travelling in the Russian Federation.

I just finished a book in that last category: Daniel Kalder's Lost Cosomonaut: Observations of an Anti-Tourist. I discovered it in a review at the Times Literary Supplement website. It is his first book in what I hope will be a prolific career. Kalder is a 20something Scot who has just returned from a five year stint working and travelling in the Russian Federation. Kalder was not your typical tourist. He consciously rejected the I came, I partied, I got laid invasion route preferred by the Eurotrash. Instead, Kalder went to places that aren't listed in the Lonely Planet and Let's Go travel guides.

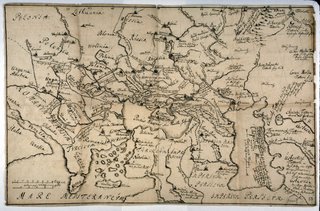

Kalder was not your typical tourist. He consciously rejected the I came, I partied, I got laid invasion route preferred by the Eurotrash. Instead, Kalder went to places that aren't listed in the Lonely Planet and Let's Go travel guides. Finding his four destinations on current maps ain't easy. Tatarstan, Kalmykia, Mari El, and Udmurtia lie along the lower end of the Volga River. Huddled in the southeastern corner of Russia, these semi-autonomous republics are largely ignored by Moscow and entirely forgotten the rest of the world. Together they are part of what Kalder calls Shadow Europe.

Finding his four destinations on current maps ain't easy. Tatarstan, Kalmykia, Mari El, and Udmurtia lie along the lower end of the Volga River. Huddled in the southeastern corner of Russia, these semi-autonomous republics are largely ignored by Moscow and entirely forgotten the rest of the world. Together they are part of what Kalder calls Shadow Europe. But adventure tourists beware! There is absolutely nothing to recommend these tiny republics. Whatever local authenticity there might have been faded long ago. The Russian Empire nearly wipped out the local pagan religions by imposing Orthodox Christianity. Later, the Soviet Union cruelly deported most of the native populations, replacing them with Russian settlers. Despite token Soviet efforts to promote quaint folk arts and crafts there was no room in the workers' paradise for authentic cultural diversity. Today, daily life is terribly nasty, thoroughly brutish, and desparately short.

But adventure tourists beware! There is absolutely nothing to recommend these tiny republics. Whatever local authenticity there might have been faded long ago. The Russian Empire nearly wipped out the local pagan religions by imposing Orthodox Christianity. Later, the Soviet Union cruelly deported most of the native populations, replacing them with Russian settlers. Despite token Soviet efforts to promote quaint folk arts and crafts there was no room in the workers' paradise for authentic cultural diversity. Today, daily life is terribly nasty, thoroughly brutish, and desparately short. Drawn to this Shadow Europe, Kalder is an anti-tourist. That makes his first book a uniquely fresh travelogue. During an all-night bender with fellow-travellers in Shymkent, the capital of South Kazakhstan Province, he declares the principles of Anti-Tourism.

Drawn to this Shadow Europe, Kalder is an anti-tourist. That makes his first book a uniquely fresh travelogue. During an all-night bender with fellow-travellers in Shymkent, the capital of South Kazakhstan Province, he declares the principles of Anti-Tourism.As the world has become smaller so its wonders have diminished. There is nothing amazing about the Great Wall of China, the Taj Mahal, or the Pyramids of Egypt. They are as banal and familiar as the face of a Cornflakes Packet.

Consequently the true unknown frontiers lie elsewhere.

The duty of the traveller therefore is to open up new zones of experience. In our over explored world these must of necessity be wastelands, black holes, and grim urban blackspots: all the places which, ordinarily, people choose to avoid.

The only true voyagers, therefore, are anti- tourists. Following this logic we declare that:

- The anti-tourist does not visit places that are in any way desirable.

- The anti-tourist eschews comfort.

- The anti-tourist embraces hunger and hallucinations and shit hotels.

- The anti-tourist seeks locked doors and demolished buildings.

- The anti-tourist scorns the bluster and bravado of the daredevil, who attempts to penetrate danger zones such as Afghanistan. The only thing that lies behind this is vanity and a desire to brag.

- The anti-tourist travels at the wrong time of year.

- The anti-tourist prefers dead things to living ones.

- The anti-tourist is humble and seeks invisibility.

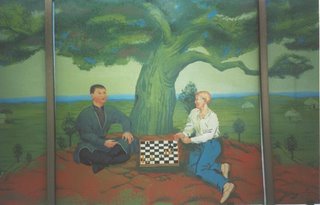

- The anti-tourist is interested only in hidden histories, in delightful obscurities, in bad art.

- The anti-tourist believes beauty is in the street.

- The anti-tourist holds that whatever travel does, it rarely broadens the mind.

- The anti-tourist values disorientation over enlightenment.

- The anti-tourist loves truth, but he is also partial to lies. Especially his own.

What fascinates me about all this is Kalder's resemblance to Isaiah Berlin. Like Berlin, Kalder is a classic fox with a passion for seemingly contradictory, otherwise disconnected, things. Although he claims no interest in local history or current events, the book betrays a widely read, curious mind.

What fascinates me about all this is Kalder's resemblance to Isaiah Berlin. Like Berlin, Kalder is a classic fox with a passion for seemingly contradictory, otherwise disconnected, things. Although he claims no interest in local history or current events, the book betrays a widely read, curious mind. Kalder's voracious curiosity for the dark corners of humanity also parallels Berlin. The latter's defense of a live and let live liberalism was strongest when he invesitgated its obscure opponents. And to be frank, Berlin's descriptions of them were often more fascinating and ultimately more instructive than those of liberalism's defenders.

Kalder's voracious curiosity for the dark corners of humanity also parallels Berlin. The latter's defense of a live and let live liberalism was strongest when he invesitgated its obscure opponents. And to be frank, Berlin's descriptions of them were often more fascinating and ultimately more instructive than those of liberalism's defenders. Perhaps it is their roles as consummate outiders; the Scottish European in southeastern Russia and the Latvian Jew in western Europe, that compels both Kalder and Berlin to explore of the shadowlands in the first place. Perhaps it also the source of their profound sympathies for lonely communities that struggle daily for survival largely unappreciated, if not unseen, by the wider world.

Perhaps it is their roles as consummate outiders; the Scottish European in southeastern Russia and the Latvian Jew in western Europe, that compels both Kalder and Berlin to explore of the shadowlands in the first place. Perhaps it also the source of their profound sympathies for lonely communities that struggle daily for survival largely unappreciated, if not unseen, by the wider world.So why read The Lost Cosmonaut?

First, you'll discover the reason for its peculiar title. Second, you'll learn how not to be an asshole in other people's countries. Finally, it may convince you that going native in a desperate search for intimate connections is a contemptible delusion even for Kalder:

First, you'll discover the reason for its peculiar title. Second, you'll learn how not to be an asshole in other people's countries. Finally, it may convince you that going native in a desperate search for intimate connections is a contemptible delusion even for Kalder:I didn't want to be a tourist. I wanted to be something more. But how can you ever be anything more than a tourist when you know you can leave? When you know, not that your stay is temporary, but that it need never not be temporary?

Labels: books, history, Isaiah Berlin, new urbanism, worldbeat, writing

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home